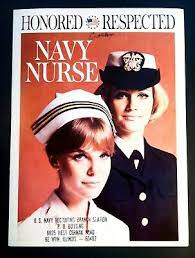

Upholding the Tradition of Navy Nurses -

Caretakers and Fighters

by Sue Wolinsky, Family Member, Army IL National Guard

She is part of the centuries-old tradition of women caring for wounded soldiers and sailors; from just after the founding of this country, through the Civil War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Middle East conflicts that the United States military has supported. (See related article on history of the US Navy Nurse Corps, in our June newsletter. June 12 is Women Veterans Day.)

Yet, when she enlisted to become a US Navy nurse in the mid-1960’s, it didn’t seem like part of a long-standing tradition. It was an opportunity for her to finish nursing school with less debt and to avoid returning home after graduation. “Like many then and now, I came from a dysfunctional family. The military gave me an opportunity to avoid going back to that life in New Jersey,” she said.

Yet, when she enlisted to become a US Navy nurse in the mid-1960’s, it didn’t seem like part of a long-standing tradition. It was an opportunity for her to finish nursing school with less debt and to avoid returning home after graduation. “Like many then and now, I came from a dysfunctional family. The military gave me an opportunity to avoid going back to that life in New Jersey,” she said.

The year she enlisted, 1965, was the same year that the US sent active combat units to Vietnam. “The Navy contacted me at the start of my final year in nursing school at the University of Maryland. They were short of nurses. They offered to pay for my tuition in my final year, so I took their offer. I enlisted as an E-3 while in school. After I graduated, my girlfriend (who enlisted with me) and I took the summer off. We went on active duty in October, attending Officers Candidate School at Naval Station Newport, RI. Then we were commissioned as Ensigns and assigned to Great Lakes Naval Base north of Chicago on Lake Michigan,” she explained. “That’s where I served during my time in the Navy.”

(Much of the media coverage of Navy nurses during that time focused on

those who served in Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries.)

She was promoted to Lieutenant Junior Grade (LTJG, 0-2) while on active duty. When her two-year commitment was over, the Navy asked her to stay in, but she declined. She ended her active duty in October 1967 and transferred to the US Navy Reserves in an inactive status for a few more years.

During her tour of duty at Great Lakes, she cared for US Navy sailors wounded in Vietnam. There she learned of many sailors’ strong desire to be healed enough so they could rejoin their buddies in their units still fighting in Vietnam. “At first I didn’t understand why they wanted to risk further harm by returning to combat duty, but then I realized how strong their bonds of friendship had become while fighting together,” she said.

The US participation in the Vietnam War lasted two decades, took over 58,000 US military lives and eventually tore this country apart. “Sailors were getting wounded, I know,” said Valerie of her time in service. “But I didn’t realize the magnitude of the war’s impact on the sailors and soldiers who served until much later, as I was studying for my master’s degree in counseling at Ball State in Indiana. That realization at that time planted the seed for the political involvement for change that I eventually dedicated my life to,” she reflected.

Valerie met her husband while in the Navy. They had a son in Indiana in 1972 and later divorced. In her civilian career, she has been a school nurse and a public health nurse, then worked as a psychiatric nurse. She came to New Mexico in 1991 and stayed. She worked with teens at a facility located between Santa Fe and Taos that had been a ranch and was converted to an adolescent psych unit. They also took in teens who were in gangs and did not necessarily belong in a psych unit, which made working at the facility less safe than other facilities where Valerie had worked.

Therefore, she left after several months and a little later learned it was shut down for alleged Medicaid fraud.

She since has worked as a supervisory nurse in a medium security unit at the NM State Penitentiary and then as a school nurse for Albuquerque Public Schools (APS). She retired from APS in 2011.

While in New Mexico, Valerie successfully maneuvered through the confounding process of adopting a daughter from Russia. “Because I was over 50 years old when I applied,” she said, “I didn’t qualify to adopt a girl from a large city like Moscow. However, I was able to adopt Svetlana (she calls her Sveta) from a rural area in Russia. I had to wait until she was five years old before I could bring her to America. She had a hard time adapting to education in the US but she made it through, graduating high school in 2016. At 13, Sveta wanted to return to Russia to meet her parents.” (Valerie had learned that Sveta’s parents had put her up for adoption because they had other children and could not provide for another child.) “In the end, Sveta did not go back to Russia,” Valerie said. “She worked through it.”

Both mom and daughter have been texting a lot, sharing their thoughts about the situation in Ukraine. “We’re upset that Putin has attacked a peaceful, neighboring country without any provocation. We both agreed we’re glad that we got her safely out of Russia. Sveta doesn’t understand why Putin doesn’t get it, that the more he attacks Ukraine, the more Ukraine and other countries want to join NATO,” she concluded.

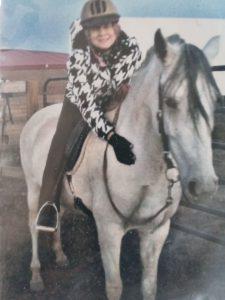

Valerie and her two children are very animal oriented. Both children are “animal whisperers,” she said with a smile. Valerie has three grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Back in the saddle and still fighting for others.

Since retiring, Valerie has devoted much of her time to “being the change” in New Mexico, and in the world, despite of having a serious brain bleed in 2018. It nearly killed her, but her tenacity and ardent advocacy for herself while undergoing treatment for several months saved her life. Recuperation took her significantly longer, with extensive support from friends.

“This only made me more fierce,” she said. She worked voraciously supporting several New Mexico progressive candidates: Deb Haaland (Secretary of the US Department of the Interior); NM Governor Michelle Lujan; US Congresswoman Melanie Stansbury; Jessica Velasquez (Chair of the Democratic Party of New Mexico), and Claudia Risner (Chair of the VMF Caucus) in her bid for a state senate seat representing rural voters in the East Mountains. Now she has two national issues she is passionate about: legal abortion and climate change.

“You know what’s come down about the US Supreme Court and the leak of their draft opinion on the Roe v Wade case? I was a nurse before Roe v Wade (case decided in 1973). I knew young ladies who died from botched illegal abortions. This is the biggest issue on my plate right now,” she adamantly confirmed.

There is an old saying that states, “You can take the person out of the place, but you can’t take the place out of the person.” One could easily extend the definition of “place” to include any major experience or passion in a person’s life. In Valerie’s case, this would be nursing and her passion for caring for people.

So this retired Navy nurse continues to match her medical knowledge and experience with her passion for helping people by fighting for social change.

History of the U.S. Navy Nurse Corps

Women worked as nurses aboard Navy ships and in Navy hospitals since the very early 1800s, yet the U.S. Navy Nurse Corps (2900s) was not formally established by an Act of Congress until 1908.

Twenty women were selected and appointed to be the official pioneers of the new Nurse Corps and they were assigned to Naval Medical School Hospital in Washington, D.C. They were nicknamed “The Sacred Twenty” and were the first women to serve formally as members of the Navy. This fledgling Corps group expanded to 160 on the eve of WWI. Their duties also expanded beyond normal hospital and clinic duties to include training natives in U.S. overseas possessions as well as training the Navy’s male enlisted medical personnel – corpsmen.