by Sue Wolinsky, Family Member, Army IL National Guard

Transgender Navy Vet Fights for Equal Rights

When you enlist in the military, you make a lot of decisions. You look at where you are in life and where you feel you should be. Then, once you get in, the military affects your life in so many ways. But sometimes you just decide to live your private life, in your own way, while your steeled exterior takes on the “something bigger than me” culture of the military.

Penn Baker, a transgender 7-year Navy veteran from the Vietnam Era, did just that. Penn served as a male in the “nuclear Navy”, under a different name, from 1963 to 1970. This was ~25 years before the US Military’s DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL policy. (The policy was in effect 1994-2011. See discussion later in this article to learn more.)

Penn transitioned to female in 1996-2000, 2+ decades after getting out of the Navy. While in the Navy, Penn met and married Dorothee. They remain married today, 53 years later.

Penn is an active member of the Veterans and Military Families Caucus (VMFC) and part of the Advocacy Committee’s effective team guiding bills through the NM Legislature that are important to our veterans and their families. Penn is also president of the Bataan Chapter of the American Veterans for Equal Rights (AVER) and is the National Transgender Liaison to AVER. “I am getting more selective in what I get involved in now, and these two organizations are the most important to me”, Penn said.

EARLY LIFE. Penn had a tough life growing up in Bay City, Michigan. “I knew I was different when I was 4 years old, later identifying as gay. I didn’t know what it was, and I didn’t have the words to talk about it. Now in hindsight, I guess my parents treated me differently because of it. In school, I got my ass whipped a couple times,” Penn recalled.

NAVY CAREER. “In the Navy, though, I learned how to fight back. When I entered basic training, I weighed 139 pounds and had a 29-inch waist. When I left basic 3 months later, I weighed 172 pounds with the same 29-inch waist. I put on a little muscle,” Penn shared, smiling.

“I wasn’t interested in (high) school; I didn’t do well. It wasn’t until I joined the Navy right out of high school and scored in the top one percentile of the ASVEB (Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery) that anyone ever said anything complimentary to me. I thought I wanted to be an underwater welder, but they put me in the Navy nuke program. I made it through nuclear power school, where the flunkout rate is 1/3 to 1/2 of the trainees, in Bainbridge, MD. By the time I finished, my brain was completely rattled. The practical part was in Sarasota Springs, NY. It’s usually a 6-month training but I got to spend 9 months there due to an overhaul. I attended sub school in Connecticut,” Penn recalled. “Navy schools’ combination of books and hands-on learning was great for me. I excelled with learning to take tests and my mechanical aptitude helped too. I always ended up at the top of the class.”

“It was interesting taking training in areas other than nuke school,” Penn mused. “When you take trainees from nuke school and put them together with trainees who didn’t score in the top 1-2%, us ‘1 per centers’ were always scoring highest in class. It was unfair to the other trainees.” Penn was assigned as a machinist’s mate on the submarine USS George Bancroft, which was under construction in Groton CT until 1965. “I stayed on that sub for the rest of the time I was in the Navy, which is not unusual.”

While in the Navy, Penn kept his/her personal life hidden from shipmates. They knew Penn as a shipmate who was married and Penn relied on a cultivated reputation as a hard nose – albeit with a lightening-quick sense of humor – to deflect any potential derogatory comments.

Penn qualified as the youngest engineering watch supervisor (at the time). “I had no problem handling that,” Penn recalled. “I leaned on my reputation of ‘it’s not good to mess with him’. I could turn from ‘fun’ to ‘you’re gonna wish you hadn’t done that’ in a split second.” Penn scored high enough on the E7 Chief Petty Officer test to be selected as CPO about 6 months before leaving the Navy in 1970. Penn was in the Navy 7 years and 3 months to complete the nuclear Navy commitment.

CIVILIAN LIFE. Penn left the Navy and used his/her Navy training and experience to work in the nuclear power plant industry, including the infamous Three Mile Island plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. “I left there 2 years before the plant released radioactive gases and radioactive iodine into the air. I opened my own machine shop in South Carolina until Three Mile Island happened; then I went back into the nuclear industry as a consultant,” Penn said.

During this time, Penn continued to grapple with sexual identity. “I was drinking heavily,” Penn admitted. “I knew I needed to do something. I heard about a doctor in Toronto who helped patients work their way through the gender confirmation process. I went to Toronto to see her. She had transitioned from male to female. That made me feel more comfortable. She told me, ‘You’re not a guy. You’re not a girl. But we’re going to find a way to help you be comfortable in the body that you are in’.” The Canadian doctor wrote a prescription for hormone therapy to be filled in the States. In 1996, Penn started hormone therapy. “I changed my name the year of my confirmation surgery in 2000. I picked Penn because it’s not male and it’s not female,” Penn explained.

“This whole thing placed an incredible strain on our marriage. Dorothee and I had to work our way through what I was doing. We went through long periods of therapy. Nothing surprises us anymore,” Penn shared.

“I ended up getting ready to do gender confirmation surgery. I was still working deeply in the nuclear industry. I was a senior project manager at the time. I thought it only fair to let my long-time employer know what I was planning to do. They sent me to talk to Human Resources in the California office. In the first of many steps they took to have my back, they transferred me from consulting to a less-public role as manager of nuclear computer data hosting. The company was trying to support me, and I appreciated that. My boss assigned one specific person to handle my health insurance. He also contacted the insurance company to get one person to handle all my claims. In the end, they paid for 80% of my surgery,” Penn said, smiling.

“Later on, I asked my boss why he backed me through all of this. He looked at me and he said, ‘we f*#*#ed up a bunch of people in the past and now I want to make it right now’.”

Penn moved to New Mexico in 1998 and eventually retired in 2020.

Penn admires the tenacity of Steve Loomis, one of the founders of NM Bataan Chapter of AVER in 1992. He was a gay man in the Army. When his house burned down, firemen turned up evidence that he was gay. He got kicked out of the Army five days before he retired. He sued the Army and finally got his pension and back pay through a court order. Steve Loomis has been interviewed on 60 Minutes. To learn about this courageous hero, click here (Past President – American Veterans for Equal Rights. We Are You! (aver.us).

Penn joined the Bataan Chapter in 2004. They marched on Washington twice and worked with both the US House and Senate to repeal DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL. When the policy was repealed in 2011, reporters descended on Loomis’ house for comment. “We were pretty elated,” Penn shared.

The Bataan Chapter provides a color guard for the Pride ABQ parade every year. “I had sign that said ‘A CLEAN SWEEP,’ using a broom to represent the Navy ‘clean sweep’. I enjoyed that. But now it looks like DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL may get turned around now. It’s sad,” Penn said.

Penn continues to fight for equal rights. Penn lives by the philosophy, which ends each email: “We must not stand by and watch another’s civil rights violated and do nothing, lest we make it more likely our rights will be violated.”

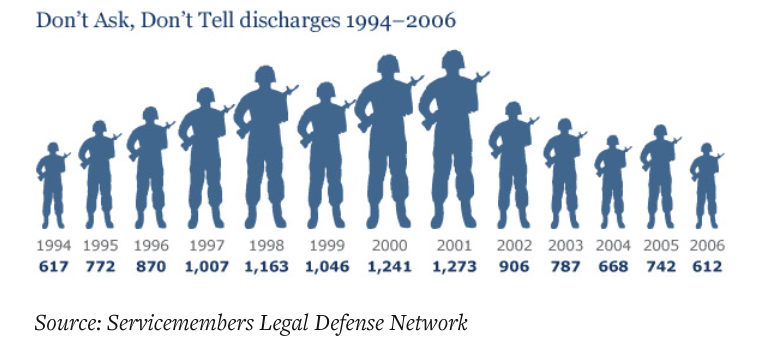

DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL. Penn experienced sexual identity issues throughout most of life and was in the Navy more than 2 decades before the military’s DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL policy went in effect in 1994. He had his transformation surgery in 2000, when the policy was in effect for then-current military members. “When I did think about the policy, I thought it was just plain stupid. First, you have so many background checks when you’re in the nuclear Navy, that they would find out everything about you at some point. The policy turned into so many witch hunts. During the time the policy was in effect (1994-2011), there were more people percentage-wise who were kicked out of the military than before,” Penn complained.

DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL cost the military dearly. “As the ground forces strive to recruit a troop strength necessary for our national security, the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy continues to undermine their efforts to attract qualified men and women. Moreover, since its enactment, this outmoded law has cost the country hundreds of millions of dollars and thousands of service men and women who were working to keep our country safe,” according to this study performed in 2009 as part of the documentation used to repeal the policy.

The Costs of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell – Center for American Progress

The Costs of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell – Center for American Progress

This policy also cost the discharged military personnel dearly. The 14,000 military personnel who were discharged for “basically being gay” under DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL lost their retirement benefits. It took 10 years after the policy ended for the Veterans Administration to reinstate their benefits. VA Offers Full Benefits To Veterans Discharged Under ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’.

In spite of the policy’s negative impact on the lives of thousands of military service personnel and the costs associated with their dismissal, some believe that the DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL policy played an essential role in the battle for LBGT+ rights in America. “The repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell in 2010 was a milestone in the fight for equal rights for multiple reasons. First, it finally allowed gay people to serve openly in the military—the quintessential macho institution. Second, it helped upend the attitude in the United States that homosexuality was best not talked about, a disorder, and a sin. And third, the repeal made clear that treating homosexuality as a reason for dismissal denied gay people equal rights, helping the fight for marriage equality pick up speed and ultimately succeed five years later,” according to the New York Times in 2021 (New ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ Account Fills Gap in LGBTQ History Books (foreignpolicy.com).

The situation today. Transgender personnel in the US military were not specifically identified when DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL was repealed. It wasn’t until then-Vice President Biden called this ‘the civil rights issue of our time’ in 2015, followed by then-President Obama’s Defense Secretary Ash Carter’s announcement that transgender soldiers could serve openly in the US military in mid-2016. This victory was short-lived, however, because then-President Trump put implementation on hold a year later. This article gives a short history of these turbulent years: How U.S. Military Policy on Transgender Personnel Changed Under Obama – The New York Times (nytimes.com). However, President Biden reversed Trump’s transgender ban on January 25, 2021, just 5 days after his inauguration. Executive Order on Enabling All Qualified Americans to Serve Their Country in Uniform | The White House.

As a side note — Penn informed me that Medicare paid for the gender confirmation surgery of an 82-year-old Army veteran in 2014 following two years of appeals. (This article verywellhealth.com explains the current process for Medicare approvals, which may vary from case to case.)

th

Thank you for your service!

-Beach